- Home

- Anita Anand

The Library Book

The Library Book Read online

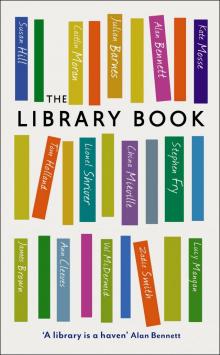

THE LIBRARY BOOK

The Library Book is published in support of

The Reading Agency

First published in 2012 by

Profile Books Ltd,

3A Exmouth House,

Pine Street,

London ECIR 0JH

Copyright © in individual contributions held

by the author

A complete catalogue record for this book can be obtained from the British Library on request

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 1 78125 005 1

eISBN 978 1 84765 840 1

Designed and typeset by Crow Books

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays, Bungay, Suffolk

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

Foreword

Rebecca Gray

This Place Will Lend You Books for Free

James Brown

Character Building

Anita Anand

The Defence of the Book

Julian Barnes

The Punk and Langside Library

Hardeep Singh Kohli

The Rules

Lucy Mangan

Baffled at a Bookcase

Alan Bennett

The Future of the Library

Seth Godin

Going to the Dogs

Val McDermid

I Libraries

Lionel Shriver

Have You Heard of Oscar Wilde?

Stephen Fry

The Secret Life of Libraries

Bella Bathurst

The Booksteps

China Miéville

Alma Mater

Caitlin Moran

The Library of Babylon

Tom Holland

A Corner of St James’s

Susan Hill

It Takes a Library …

Michael Brooks

The Magic Threshold

Bali Rai

Libraries Rock!

Ann Cleeves

The Five-Minute Rule

Julie Myerson

If You Tolerate This …

Nicky Wire

Library Life

Zadie Smith

The Lending Library

Kate Mosse

Fight for Libraries as You Do Freedom

Karin Slaughter

Afterword: The Reading Agency

Miranda McKearney

Contributors

Acknowledgements

FOREWORD

REBECCA GRAY

The Library Book began with a simple idea: to celebrate libraries. As the book took shape, it became clear that the value of public libraries transcends the books on the shelves. Books and stories are lifelines, and libraries house those lifelines, making them available to all. They are important not just for the books, but for the space and freedom they provide, as well as the navigation and advice provided by librarians.

I volunteer for a project run by Quaker Homeless Action, a mobile library. One of my colleagues, John, is, in his own words, a poacher-turned-gamekeeper. John used to borrow books from the library every week. The volunteers always looked forward to seeing him – he’s an enthusiastic reader, and we’d always have a good chat about the books he’d read, and what he might read next. Now he has a home, and he volunteers almost as often as he used to borrow books. Many of the people who visit us at the mobile library know John, and he’s become a bit of a draw. People come to the library to say hello, have a catch up, and often, they’ll end up borrowing a book too.

It’s perhaps surprising that about half the books we lend are returned, not a bad statistic given that most of our borrowers are itinerant. John says it’s a symbol of trust that when you’re on the streets, and someone lends you a book, it builds your confidence and becomes an emotional investment. We’ve had books returned, carefully wrapped in protective plastic, so that they’ve stayed dry when the person who read them is soaking wet from the winter weather. Sometimes, though they have nothing of their own, our readers donate the books they’ve been given elsewhere to be added to our library.

For many of us, borrowers and volunteers alike, the mobile library is a meeting point, a place where all sorts of people come together, to have conversations you’d never imagined, hear life stories that seem completely different to yours, or surprisingly familiar. Like all libraries, it’s a place where our minds open up, and the world becomes a little wider, and yet smaller too. John’s description of it is perfect: ‘You go to the library on your own, but you end up talking to people, the librarians, other readers. And a conversation about a book becomes one about life, and you leave feeling that you aren’t alone after all.’

At the library, some of the people who share our city but are mostly ignored become fellow book-lovers, and it’s a great equaliser. In the rest of their lives, they are asking for help, or being told what to do; here they are just people who are welcome to take a book. And when you take away a book, you’re taking an escape route from your own problems, or from the boredom of empty hours. John describes the library as a combination of things: it’s a place where practical things – information, face-to-face contact, filling your time – combine with elements that are harder to pin down, like escapism, imagination and comfort.

John found that, as a homeless man, he was often perceived as a threat, or a nuisance. He says that the library made him feel part of a network, he made friends, and that gave him confidence, and the ability to trust people, where he’d had none before. And those things helped him get back on track, so that now he has a place of his own, and a library card too. More than anything else though, the library has taught me and John that – with apologies for the cliché – you can never judge a book by its cover. What people want to read often seems incongruous. A pair of biker-types taking away Thoughts of the Dalai Lama. People without access to instruments requesting sheet music. Aspiring poets sharing their work and then borrowing horror stories.

Putting this book together – as well as working on the mobile library with John – has been truly enlightening. So many people who write books would never have even begun reading without the influence of these completely democratic public spaces. So many of the writers who’ve contributed describe the library as a place of liberation, a place where lives literally change, and change in a way infinitely more profound – and common – than in any other place I can think of. So I’m very grateful indeed that so many authors have kindly given their work to this book, and their royalties to The Reading Agency. That money will go to their library programmes, which are described at the end of this book. By buying, or borrowing, this book, you’re already supporting The Reading Agency, but if you’d like to know more about their work, do visit www.thereadingagency.org.uk

I hope you enjoy The Library Book.

THIS PLACE WILL LEND YOU BOOKS FOR FREE

JAMES BROWN

Do you read books? Hundreds of them? Are your shelves, rooms, bags, cars, offices full of books? Do you buy them on impulse at train stations and airports? Read the first few chapters before your journey ends? Do you come across a car-boot sale, second-hand bookshop or a charity shop; and walk away with books that look like bargains but only have a 25 per cent chance of getting read?

Do you hunger for new releases by favourite writers, get lost scouring Amazon and eBay and fan sites for rare editions, or volumes you only just heard about? Then never buy them. Go through books in a night, a week, one sitting. Lose sleep over them. Clinging on till the ver

y end. An end that leaves you in tears, angry or spent? Or do they drag on for months and months while other easier-to-digest stories come and go?

Do you look forward to holidays because you know there’ll be a literary lottery on the hotel’s second-hand library shelf? Do you buy books like a habit? Do you find it hard to move them on after you’ve read them, caught between wanting to give them to a friend, or get some of the cover value back, and wanting to retain them as a physical memory of the time you enjoyed reading them?

I do a lot of that and more. You can also add the following to books I have: presents I receive, the books I borrow from friends, and the ones that arrive from publishers and writers. But I did something on Saturday that might change all that. I joined a library. And I was shocked, exhilarated and inspired by the experience.

The library in question has been there for a short while, in the high street of a small town I visit regularly, Rye in East Sussex. It is less than a year old, a huge, clean, well-stocked affair that now sits in what used to be Woolworths. It has computers, computer games, DVDs, talking books and most importantly, books. Thousands of them and, as my son, my girlfriend and I all individually noticed, hardly any of the books have ever been taken out. It couldn’t be more different from the libraries I remember from years gone by.

When I suggested joining the library my girlfriend laughed at me, and accused me of looking for a money-saving scheme, but it just seemed to make sense. I’d walked past this big double-fronted shop full of literature many times and hadn’t bothered to venture in. Meanwhile I was suggesting going to a table sale just to see if an old lady I’d once talked to had any more Rebus crime novels and the g/f was getting antsy because she’d run out of books by an author she was consuming at a rate of one every forty-eight hours.

I’ve not been a member of a library since I was about ten years old so I wasn’t too sure what to expect, but I figured you’d have to pay something to join and something to take each book out and it would take ages like everything else does to join or sign up for nowadays. So I was stunned when the lady behind the counter explained it was free to take a book out, free to join and you could prolong your borrowing of a particular book beyond the three-week deadline online. Plus you can order a book and they’ll get it in for you for 80p. So that was it, all of it’s free. No wonder those that use libraries regularly are up in arms about proposed closures of them. It just strikes me as something a nation can boast about – we lend people books for free.

A couple of forms filled in, a card signed, a proof of address and boom we were in. Crime books – masses of them – le Carré, Michael Connelly, Elmore Leonard, James Ellroy, David Peace. History books, war books, books by Sabotage Times writers, sports books. I’m not too sure what my girlfriend was examining at the time, but my son was just staring at all the books and films, wondering what to take. It was like being in Waterstones, but free. Eventually I had to call time on the browsing as we were running out of reading hours. We left with a Michael Connolly thriller, an early le Carré novel, a kids’ book and the Diary of A Wimpy Kid film.

Back home to read, great books in hand, no money spent and knowing the house won’t have yet more books in that no one else ever gets to read. Next time you’re driving or walking past your local library maybe break the habit and step inside. It’s even cheaper than Amazon.

CHARACTER BUILDING

ANITA ANAND

I still can’t open a book without smelling chlorine and tomato soup. It was a ritual for us throughout our childhood. Three noisy siblings being taken by a weary mother for a weekend of character building. First there was swimming at the Loughton swimming pools, where bombing and heavy petting were strictly prohibited, but running around the pool was largely ignored by the indifferent Essex lifeguards. Then instant soup from the machines in the foyer. The fewer powdery lumps at the bottom of the plastic cup, the luckier the week ahead was going to be.

And then, best bit of all. The part that made the stinging eyes, lumpy soup and clammy, clinging tights all worthwhile. The library was the best place in the world. A labyrinth of shelves where you could lose your mother and then lose yourself in a book of Greek myths, or somebody’s struggle to find love in class 5C or the life-cycle of a ladybird. At the age of around seven, I had decided that I would read every single book in Loughton Library. And at first the mission was a febrile one. My poor mum would find me behind two piles of books, refusing to go home unless I could finish reading the one pile and take the other home. I’m certain my present and permanent shoulder ache is a result of winning those weekly battles and the hefting that came with such victory.

During that time, an awkward schoolgirl (who found herself out of the class more than in it – normally excluded for chatting and generally irritating behaviour), made friends with minotaurs, furies, gorgons and chimeras. They were similarly disruptive and, I thought, similarly misunderstood. Then the busy world of Richard Scarry, everything Narnia related, books about frogs and dogs and plants that ate flies and anything Roald Dahl could think of. And for about a year, absolutely anything to do with stars and planets and the night sky. I threw myself into Charlotte’s Web and cut my way out waving a Silver Sword.

The library became the cathedral where I would come to worship and the stories were as precious to me as prayers. As I grew older my tastes became more discriminate. Instead of trying to read everything I could, I sought out the books I heard the ‘cool people’ talking about. The teachers who I liked, programmes on the TV that sounded clever. Basically, all wonderful, and all extra-curricular. The library was my partner-in-crime. When I should have been reading Jane Austen, it aided and abetted me to read Sylvia Plath. We were naughty together, the library and me. I would show it my membership card and it would show me the world.

When I was a little older, maybe thirteen or fourteen and ‘deep’, there was a habit I picked up at Loughton Library that I would have still today, if the world were a less computerised place. At the back of each book used to be a slip of paper which had the date stamps, detailing all the times the books had been released into the wild. I remember in my early teens taking books from the shelves and only checking out those that had sat unread for five years or more. I did it because I couldn’t bear the idea of any part of that place being neglected and unloved. In return the library took me on adventures that not even the ‘cool people’ could have warned me about. I went on obscure adventures up the Ganges river, learned the rituals of Hasidic Jews and got some way through the once extolled merits of electroshock therapy (I’m not really surprised that book didn’t have much of a social life).

The library is a different one now, and I cannot claim to be as ‘deep’, but I love taking my son to our local. We choose our piles with great care and excitement. He’s one and a half, and I am pleased to report that so far we have learned that Spot loves his mum and Spot loves his dad, and Caterpillars can be very hungry indeed. As can children, as long as libraries exist to feed them.

THE DEFENCE OF THE BOOK

JULIAN BARNES

From a proposed second edition of England, England

(As Sir Jack Pitman’s project for a replica version of England on the Isle of Wight proves an enormous commercial success, the mainland, or ‘Old England’ as it has come to be known, goes into sharp decline …)

… The first signs had been misleading, and greeted by some islanders with delight. After Scotland and Wales had left the Union, and Northern Ireland been reunited with the Republic, Europe lost patience with the sulky rump that remained. Decades of carping from the sidelines, while constantly demanding special favours and the repatriation of powers, were finally repaid. Germany and France, strongly backed by Europe’s newest Celtic adherents, led a swift campaign to evict England. ‘At last’, as the ninety-three-year-old European President-for-Life Angela Merkel put it, ‘we are repatriating to you your powers, and not just the ones you asked for, but all the other ones as well.’

There was much

excitement, as the country, having become smaller and less influential, had also become more xenophobic. The Daily Mail which, after the demise of The Times, was widely referred to as ‘the newspaper of record’, funded street parties and firework displays. But the euphoria was brief. Europe, not content just to evict England, also wanted to bring her low. Subtle and sometimes unsubtle trade barriers were raised; appeals to international organisations against such tariffs failed. The United States had long been looking westward, and now tended to regard England as an embarrassing ancestor, and a case for humane termination.

Trade collapsed, and the nation’s infrastructure with it. The Health Service, long privatised, had become known to the poor as the Death Service, since the government was now only responsible for the minimal duty to dispose of dead bodies. For the few surviving rich, there were regular flights to the continent, from which they returned with new German hips, cataract-free Czech eyes, and all manner of French cosmetic enhancement. Pensions were no longer paid, and rubbish no longer collected. Looted and burnt-out shops were a common sight; communities gated themselves in; armed guards protected allotments at night.

Poverty threw up a few improvements, like the renaissance of the canal system. The re-establishment of the old barter system was welcomed by many. But it was the Defence of the Book that caused the most surprise. The widespread library protests of the early 2010s, more than a generation back, meant that much of the service had then been saved, an outcome for which all three parties had taken the credit (though it was thought that the ritual suicides of three novelists and a poet outside the Houses of Parliament had proved the tipping point). But little opposition was expected when the National Coalition announced that every remaining library was to be closed within a month. Since the digitalisation of all forms of information, libraries – like churches under Communism – were inhabited mainly by the elderly, that last generation which held on to the idea of the physical book as an item of value in itself.

The Patient Assassin

The Patient Assassin The Library Book

The Library Book